The wheelbarrow has been a widespread device of transportation for about two thousand years of Chinese history. It seems to be an indigenous invention, as it already appears in Han times – about a millennium earlier than in Europe – and moreover possesses unique constructional features enabling it to transport much heavier weights than its European counterpart. My article briefly outlines the technological evolution of the Chinese wheelbarrow and analyses modes of its representation, using archaeological and pictorial as well as textual evidence. Set against this historical and cultural background, the focus is on the use of the wheelbarrow as a motif in folk prints since Late Imperial China, along with an iconological analysis of other major pictorial elements of the prints. The article also introduces the main contexts in which wheelbarrows occur in woodblock prints. Aparts from pseudo-realistic settings, wheelbarrows most prominently appear in the narratives "The Marauding Monkeys," "Testing Zhaozhou Bridge," and "Coming Home with Riches." Although wheelbarrows fulfill different functions in each of these narratives, they are always associated with the mercantile sphere or the idea of prosperity. Additional legitimization of this traditionally not highly esteemed sphere is procured by the association of this humble means of transportation with two future emperors, Chai Rong and Zhao Kuangyin. The wheelbarrow in popular prints is not only loaded with baggage, hats, magical mountains or other treasures, it is also loaded with meaning and can thus be called an auspicious symbol of prosperity and social advancement.

Images

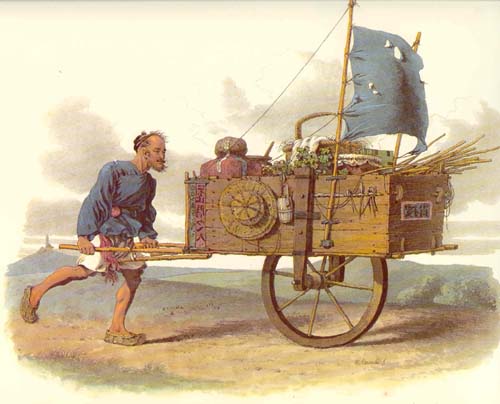

Fig. 1: Water color by William Alexander, c. 1800 (Alexander/Mason 1988: 89)

Fig. 2: Transportation of coal, Shandong, c. 1900 (Hinz/Lind 1998: 161)

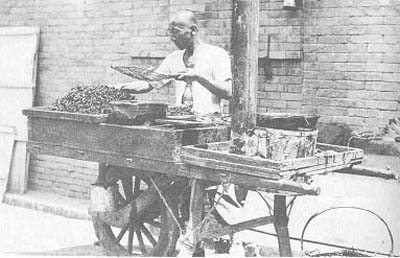

Fig. 3: Peddling fried shrimps, Peking, early 20th century (Beijing jiu ying 1989: #163)

Fig. 4: Transportation of passengers, John Thomson (*1837), c. 1868 (Goodrich/Cameron 1999: 67)

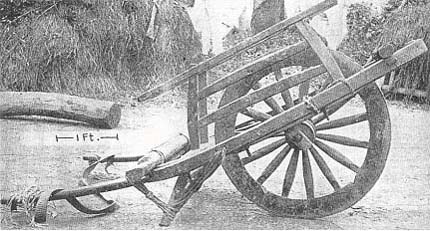

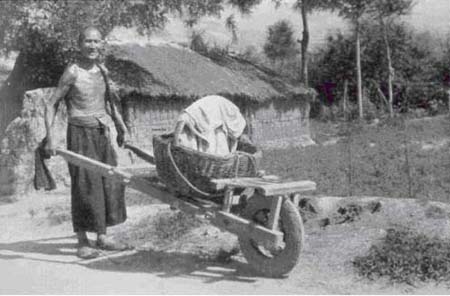

Fig. 5: Jiangxi, early 20th century (Hommel 1937: 321f.)

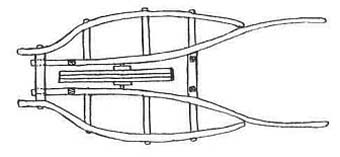

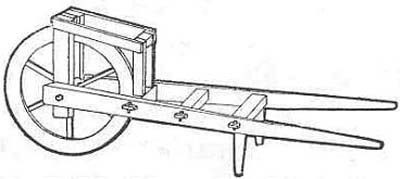

Fig. 6: Two Types of wheelbarrows (Cf. Needham 1965: 270)

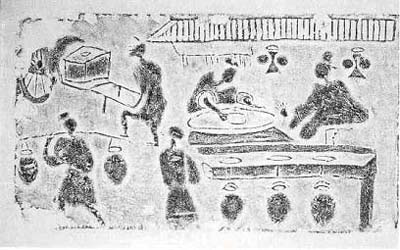

Fig. 7: Reconstruction of a Western Han wheelbarrow (Sun Ji 1991: 117)

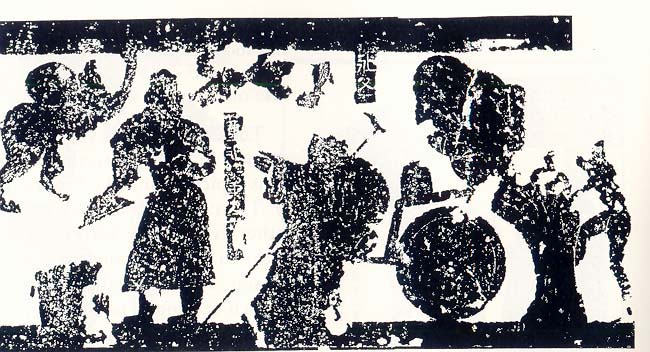

Fig. 8: Distillery, rubbing of a pottery relief, Sichuan, 1st/2nd century AD (Goepper 1995: 404)

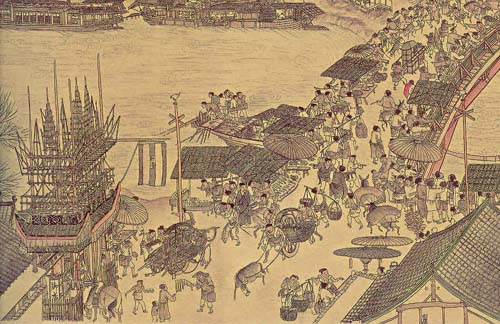

Fig. 9: Story of Dong Yong, rubbing of a stone relief, Shandong, c. AD 150 (Nagahiro 1965: 80)

Fig. 10: Zhang Zeduan, "Qingming shanghe tu," 12th century, detail (Zhang Anzhi 1979: plate 5)

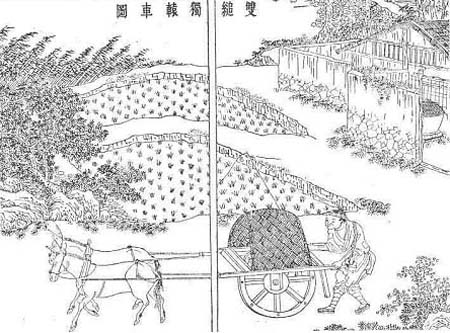

Fig. 11: Northern (left) and Southern (right) wheelbarrow, Tiangong kaiwu, 1637 ( Jiaozheng Tiangong kaiwu 9: 188ff.)

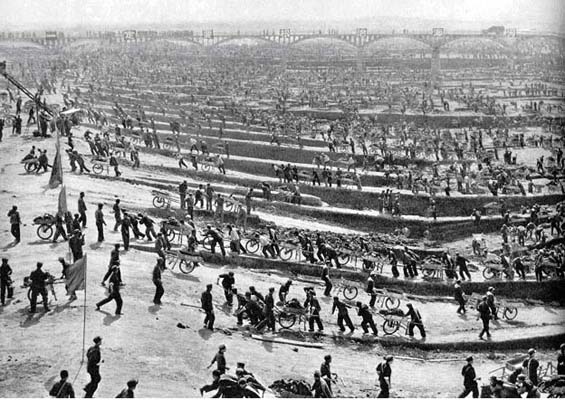

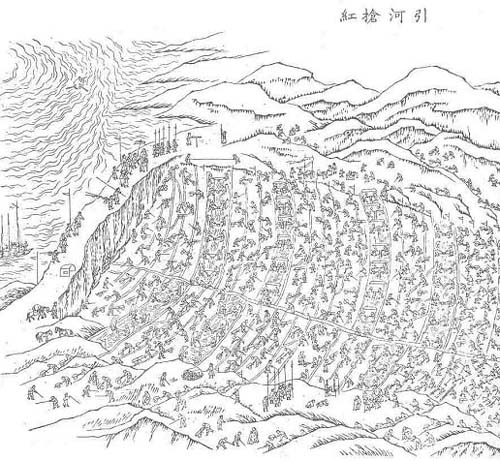

Fig. 12: Application of wheelbarrows during flood control projects, Shandong, before 1973

( Jinian Mao zhuxi 'Yiding yao genzhi Haihe' tici shi zhou nian yingji 1963–1973 : 60/61, 118)

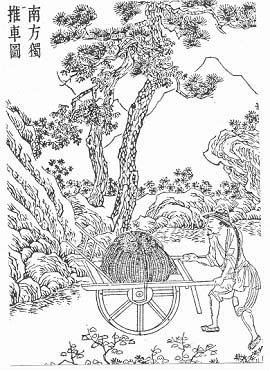

Fig. 13: Shanxi, 1958 (Needham 1965: #512)

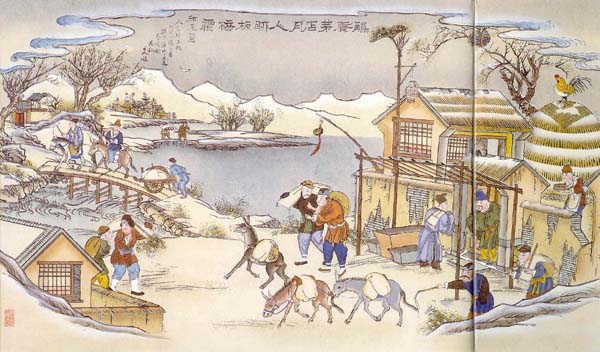

Fig. 14: Building a canal, woodcut, c. 1833–1842 (Needham 1971: 262)

Fig. 15: Application of wheelbarrows during flood control projects (Ebrey 1999: 311, Detail)

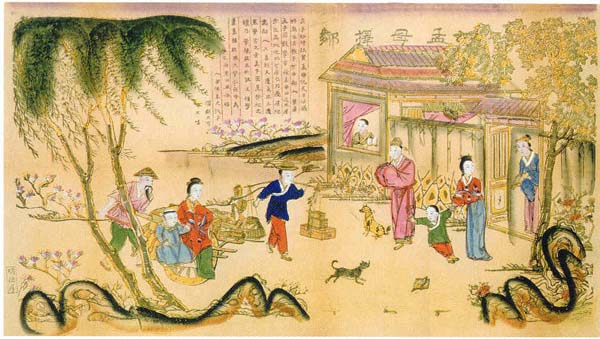

Fig. 16: "Picture of travelling," Yangliuqing, Hebei, Qing (no. I)

Fig. 17: "Mother Meng chooses new neighbors," Yangliuqing, Hebei, Qing (no. IV)

Fig. 18: "Monkeys robbing straw hats," Yangjiabu, Shandong, Qing (no. VI)

Fig. 19: "Marauding monkeys," Shenmu, Shaanxi (no. IX)

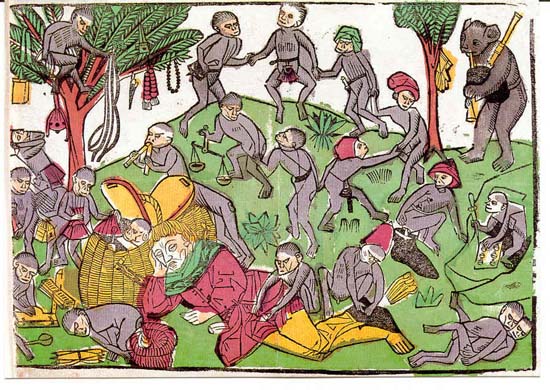

Fig. 20: "Monkeys plunder a sleeping peddler," unidentified German master, color woodcut, c. 1480/90

(Kupferstichkabinett Schloß Friedenstein, Gotha)

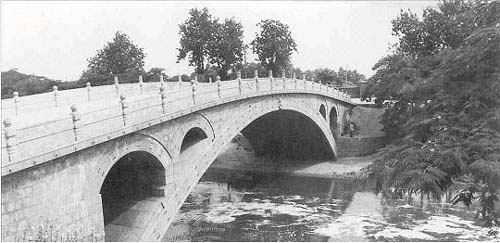

Fig. 21: Zhaozhou bridge, Hebei (Ebrey 1999: 116)

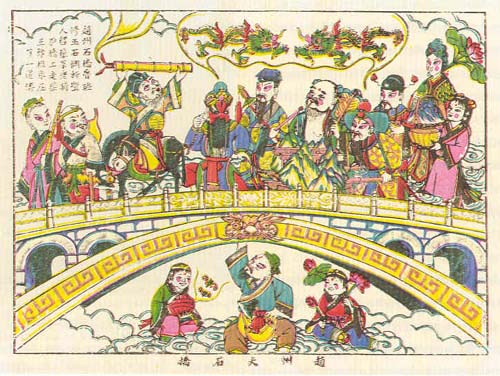

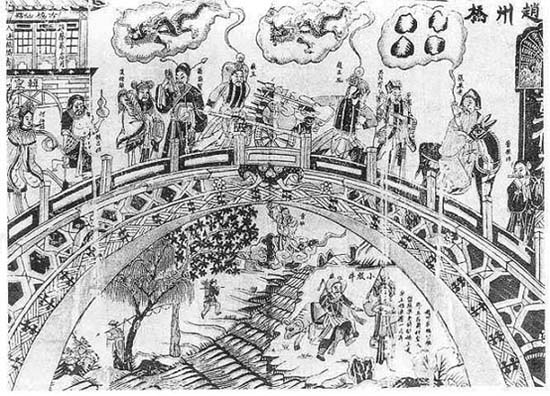

Fig. 22: "Zhaozhou bridge," Yangliuqing, Hebei, Qing (no. XII)

Fig. 23: "The great stone bridge of Zhaozhou," Wuqiang, Hebei (no. XIII)

Fig. 24: "Zhaozhou bridge" (no. XVII)

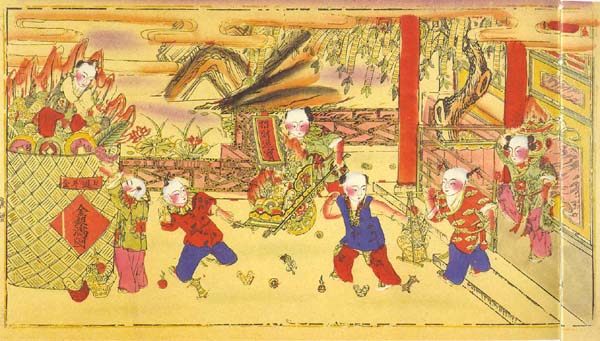

Fig. 25: "Coming home with riches," Weixian, Shandong (no. XXI)

Fig. 26: "Riches are attracted, treasures come in," Yangliuqing, Hebei, Qing (no. XXV)

Fig. 27: "Cornucupia," Taohuawu, Jiangsu (no. XXVIII)

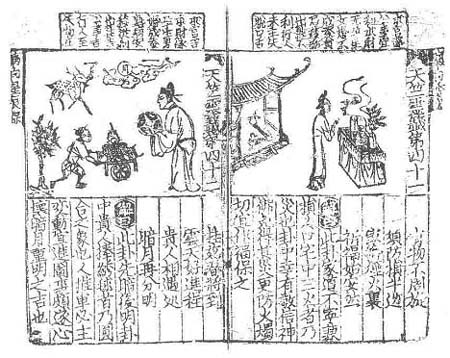

Fig. 28: Illustration from Tianzhu lingqian (Hegel 1998: 171)

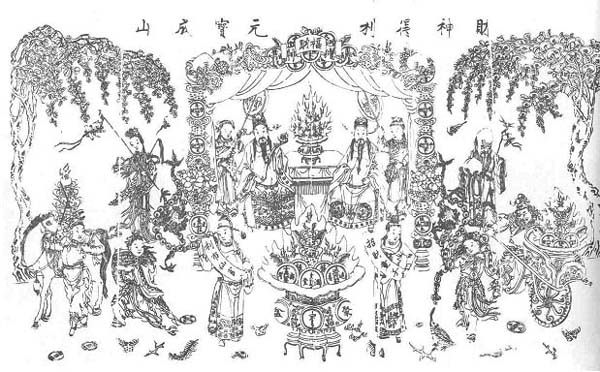

Fig. 29: "Gods of wealth achieve profits, ingots are mounting up," Yangliuqing, Hebei (no. XXXI)

Fig. 30: "Coming home with riches," Weixian, Shandong, Qing (no. XL)

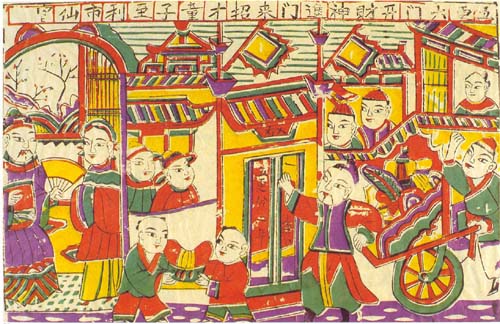

Fig. 31: "The god of wealth enters the door," Yangjiabu, Shandong, Qing (no. XLIII)

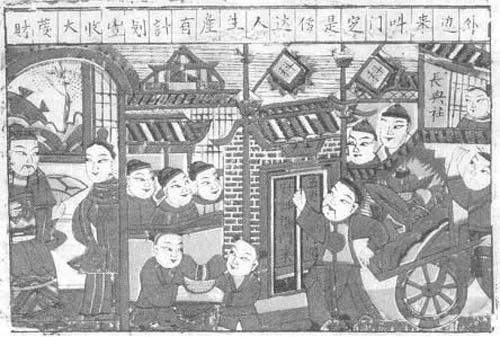

Fig. 32: "The god of wealth enters the door," Yangjiabu, Shandong (no. XLIV)

Fig. 33: Door god, Dali, Yunnan, 1992 (photograph by the author)

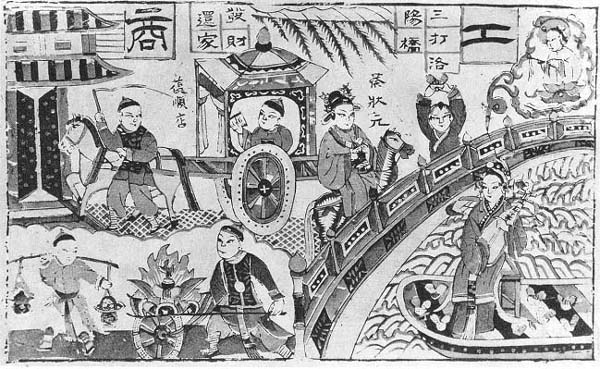

Fig. 34: "Picture of the four classes: merchants and artisans," Weixian, Shandong (no. XLV)